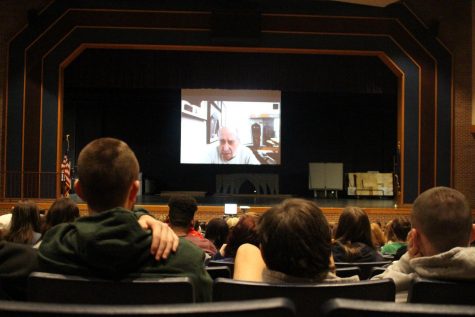

Holocaust Survivor David Tuck Speaks with Students

“It’s hard for me to believe it myself, being able to sit here and speak to you today.”

David Tuck, a 91-year-old Holocaust survivor, said as he Skyped with an array of Susquehannock students on Jan. 30.

Tuck explained how he originally lived in Poland, a country with a population of 34 million at the time.

“10% of the population was Jewish. 3,200,00 didn’t make it back [after the Holocaust],” said Tuck.

Growing up was a little different. “We had to wear the yellow armbands that had the star of David on the front and back. And they soon gave us numbers. A year after that…we had a friend of ours tell us that we had to move. Leave our homes and go to a ghetto,” said Tuck.

When Tuck and his family arrived, they were told where and how to live.

One day he and his father were asked to be interviewed since they were able to speak and understand German.

After his father’s interview, Tuck was approached and was asked how old he was.

“I said I would be turning 10 in December, and he [the German soldier] said, ‘No, fifteen,’” said Tuck.

Tuck later learned that the Germans had no use for children, but once the Jews reached the age of fifteen, they were able to work; so upon being told he was fifteen, he was now fifteen in the eyes of the Germans.

For a year he was forced to work as a machine mechanic in a labor camp, which threw him into a premature adulthood.

His diet only consisted of bread and soup seemingly made of mostly water and coffee.

He would hide extra bread stolen for him by a friend in his shirt and slowly nibble on it throughout his day to make it last longer.

“One day I made a mistake of hiding the bread, and someone caught me. I was worried because if he [the commander] would step on me he would crush me because I was losing weight so fast.” said Tuck.

“The guy asked me, ‘Who gave you the bread?’ because it was white. Our bread that was given to us was always brown,” said Tuck. “And of course I didn’t tell on the guy that gave me the bread, but the man must have seen what was happening and took care of it.”

Tuck soon created a strategy of survival in the camp he was in by asking to help the commanders, so he could get more scraps of their food.

Many times he would have to eat the food straight from the trash can. “They always laughed at me when I would dig around. This went on for a long time,” said Tuck.

A few weeks later everyone in the labor camps was told that the Americans landed in Europe and the Russians were coming.

He had spent two years in this camp and soon was taken to Auschwitz by train car.

It was a three day trip with no windows or bathrooms.

Tuck soon was given a new identity which was tattooed on his arm, No.141631.

Along with his number he was given a cup, a plate and a striped outfit.

“We had no pillows; many of us used our plates that we would eat from,” said Tuck.

Despite living in the horrifying camp, Tuck soon was free from Auschwitz when he was rescued by the Americans on May 7, 1945.

He was able to become healthy and travelled to France where he met his future wife, Marie, who he soon took with him to America.

“It was hard at first, trying to get back to normal. But I told myself, I have to live. I cannot live if I keep this on me and in my mind. I had to force myself to slowly move on and be better. And I did,” said Tuck.

Tuck tells his story in hopes of showing students how important it is to not live in a world of hate.

“If you live your life full of hate, it will destroy you,” said Tuck.

He also expressed how important it is, in the end, to focus on one’s education.

“If there is only one thing you take from me talking to you today, let it be your ability to further your education. Education is the most important thing in one’s life. You can go anywhere, do anything with an education. Stay with it,” said Tuck.

It is now close to the 75th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz, and parts of Europe and the United States seem to have a concerning idea of the resurrection of anti-semitism.

“I fear the idea that this anti-semitism could possibly be returning,” said Tuck. “I fear that we as a world have forgotten what happened, and I do not want to imagine that all of this could return again. You would think, haven’t we learned. We say ‘Never Again,’ but I don’t really know anymore and that scares me. I pray to God everyday saying,’Please do not let this happen again, it can’t happen again.'”

Senior Emily Polanowski is the C0-Editor In Chief for the Courier staff this year. She finds article writing and video to be her favorite mediums. Outside...